Our trip to Tianjin and Binhai showed us two different chapters of Chinese history, allowing our group to gain a better understanding of the domestic narrative of Chinese history. The first day, we traveled to the Tianjin History Museum and several concessions previously held by Western powers and Japan. On the second day, we visited a handful of highly successful Chinese companies who had recently gained a global market. Seeing these two sides of China, the past and the present, fit together in my mental image of China’s history and development. Our first day in Tianjin represented a snapshot into the century of humiliation, and the trip to Binhai showed China’s astonishing rebound. However, a few of the experiences gave me new insights to how Chinese history is portrayed in China.

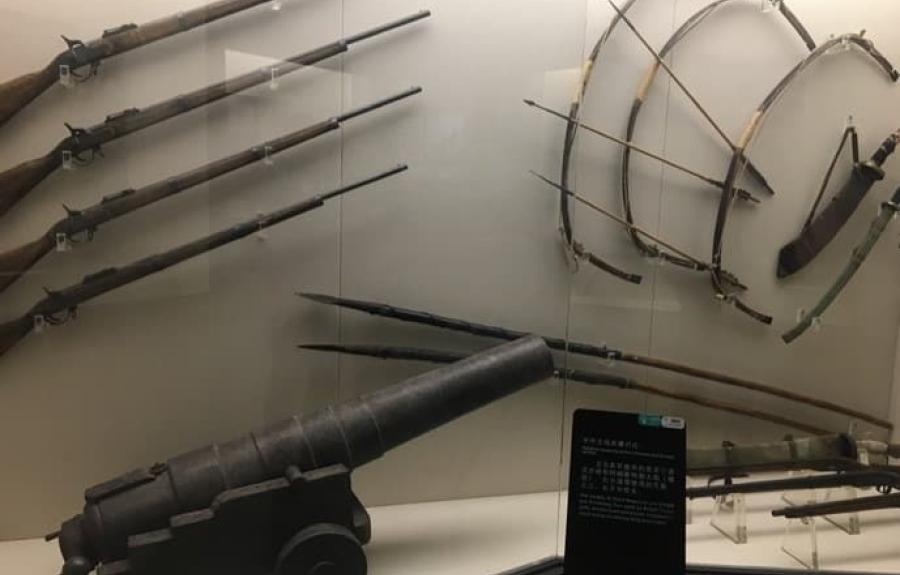

We visited an exhibit in the Tianjin History Museum titled “100 years in China,” an exhibit that detailed Chinese history from the late nineteenth century to the present. Much of the information I had already learned in Chinese history classes at Cornell, but the selection of different items and the corresponding narrative showed the Chinese perspective on their history. It was interesting to see how the century of humiliation was portrayed—I never quite understood how humiliating the invasion of Western countries was to the Chinese. A clear example of China’s feeling of backwardness during this period was the display of Western weapons compared to Chinese weapons during the first British invasions. A picture is shown at right, with British weapons on the left and Chinese weapons on the right.

What I did find odd about the museum, however, was the description of the Japanese invasion of China during World War II and the Chinese civil war between the Guomindang and the Communist Party. Rather than the museum providing a Chinese version of the events, both events were left out altogether. The narrative in the museum stopped around 1930 and continued with the victory of the Communists over the Japanese, and then the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949. The exhibit then continued on with history displays dating up until the present. I was surprised with the omission because the display seemed to give a rather unbiased and accurate account of events, with the exception of the omission of nearly two decades of history.

While taking a taxi to the Tianjin Concessions, we heard Dr. Xu’s description of the history of the concessions. While explaining the history, Dr. Xu switched between Mandarin and English, and at one point the taxi driver understood Dr. Xu and exclaimed that Dr. Xu should not be telling us about the concessions. The taxi driver felt that the concessions were humiliating, and that he wanted to personally tear the buildings down. I knew that the concessions are not exactly a celebrated part of Chinese history, but the areas in Tianjin are beautifully restored and government protected, which seemed counter to the local population’s wishes. Dr. Xu explained that the restorations hare meant to promote tourism to Tianjin. It seems like an interesting idea, to preserve the uniqueness of the architecture Italian, British, Japanese, Austrian, and other Western styles in the heart of a modern Chinese city. As a Westerner, I loved that the concessions were restored, and felt that it was a fun way to feel like I was traveling to Europe without leaving China. However, I’m surprised that the area was restored, as it seems that many other Chinese share the sentiments expressed by our taxi driver.

The day learning about Chinese history sharply juxtaposed the day in Binhai. By touring the facilities of a water robot manufacturer, a supercomputer, and a computer systems processor, it was clear to see how quickly China has transformed. Each company either developed or found success within the past decade, and each had a strong global presence. Compared to the repeated mentions of the “century of humiliation” the day before, in Binhai it was clear to see that China has truly entered a new era of progress and development.